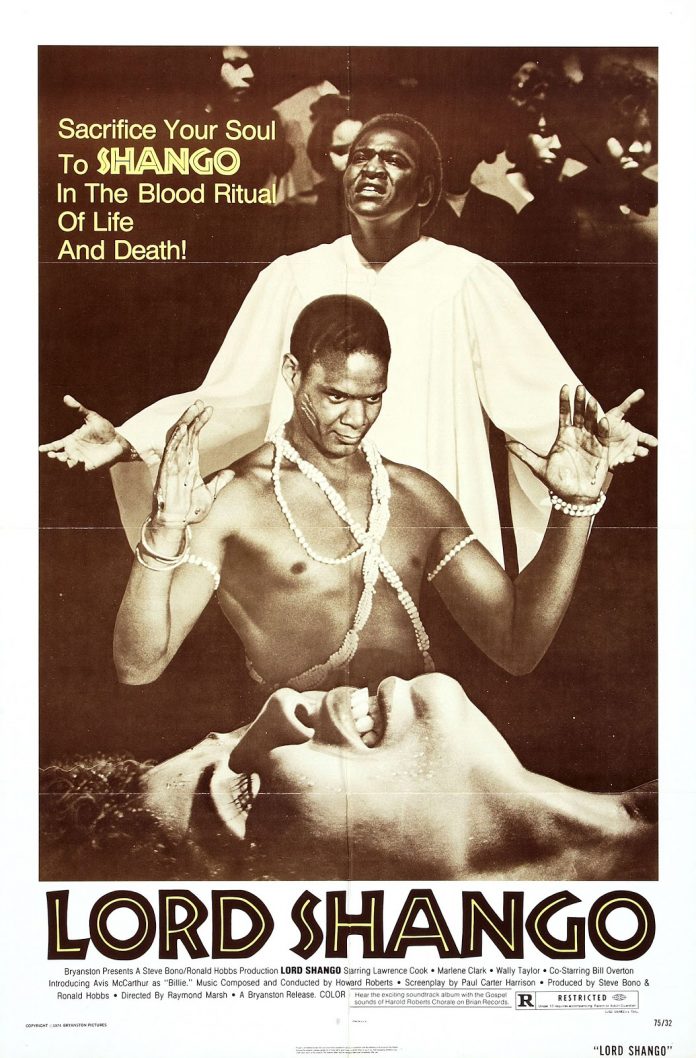

A couple of years after co-starring in the landmark black horror film Ganja & Hess, scream queen Marlene Clark headlined Lord Shango, and while Ganja & Hess has emerged from the shadows in recent years to gain some mainstream notoriety (and an ill-fated Spike Lee remake), Lord Shango remains elusive to most horror fans. True, it’s not a straightforward horror movie, but neither is Ganja & Hess; both feature a blend of heady drama, romance and social consciousness spruced up with genre trappings. While Ganja‘s supernatural themes delve into the realm of vampirism, Shango explores religion and the afterlife — spirits, deities and the like.

Clark stars as Jenny, a small-town single mother to teen Billie (Avis McCarther, who is actually more than two years OLDER than Clark). Yearning for another child, Jenny heeds the advice of her shifty boyfriend, Memphis (Wally Taylor), who suggests she let the local preacher baptize her, because…ministers know how to get their parishioners pregnant? Anyway, she takes Billie along for a buy-one-get-one-free baptism, which ticks off the girl’s boyfriend, Femi (Bill Overton), because he’s a member of a sect that practices a Yoruba religion (with perhaps some elements of voodoo) that reveres an entity known as Shango.

Femi interrupts the baptism, so the minister and his boys (including Memphis) decide he’s in need of an impromptu, forced baptism — you know, a murder. So, in front of a throng of churchgoers, they drown the boy in God’s name. Oops, our bad.

Understandably soured against Christianity, Jenny and Bille begin leaning towards the Yoruba clan, beginning with Femi’s funeral — which involves significantly more chicken blood than a typical Christian burial. Soon after, Billie begins seeing visions of Femi, leading to a case of mistaken identity in which she sleeps with Memphis. If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times: never trust a man named after a city.

Pissed, Jenny kicks him to the curb, and Billie runs away in shame. Months later (!), a desperate Jenny turns to the Yoruba sect leader, who agrees to help bring her daughter home using a ritual. It turns out a sacrifice is necessary for this to happen, so one of the church deacons who drowned Femi keels over, dead.

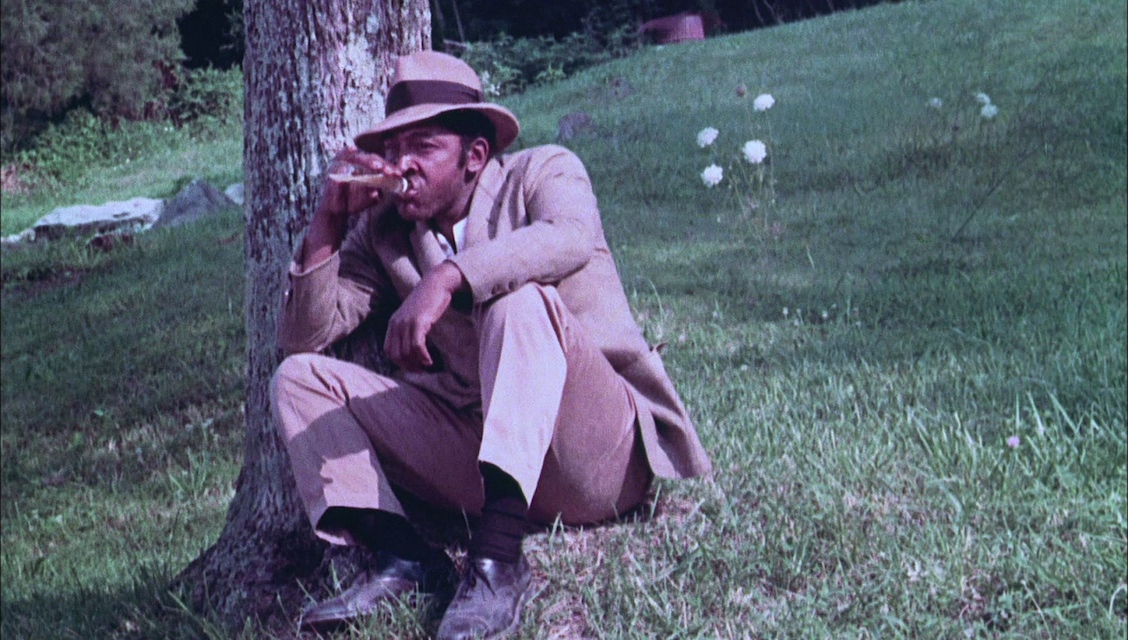

Meanwhile, Jenny’s friend, a local drunk/part-time mystic named Jabo (Lawrence Cook), torments Memphis with vague threats like, “The price of life is sacrifice” and dispenses cryptic comments to Jenny like, “There’s always a struggle when a restless soul tries to enter a body not yet born.” The implication is that he knows more than he’s letting on, and he hovers in the background as Jenny gets deeper into the African religion, continuing to request sacrifices as other church members die.

The concept of someone conjuring supernatural vengeance certainly isn’t an original trope for horror, but Lord Shango manages to stand out with its understated, non-exploitive (non-Blaxploitive?) tone. It’s got the deliberate pace of a jazz ballad and conveys some of the old-timey melodrama of the “race films” of the early 20th century from directors like Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams.

Like many of those films, it focuses on familial bonds, the power of religion and the conflicts between those of differing social statuses. What makes Lord Shango interesting is that its conflicts arise not from differences of wealth and education, but rather differences of worship and faith. And while race films tended to affirm Christian ideals, Lord Shango paints the Yoruba sect in a much better light than the traditional Christian clergy and worshippers. It’s undoubtedly a reflection of the Afrocentrism of the late ’60s and ’70s that, combined with its slow-burning pace, is perhaps another reason why the film never had a ton of commercial appeal.

As such, Lord Shango is often more admirable than entertaining. The production value is a little rough around the edges, the writing is a bit murky regarding the rules of the ceremonies/sacrifices, and compared to Ganja & Hess, it lacks a certain artistic flair. Still, it’s an important example of black horror that should hold a more prominent position than it does amongst the films of the Blaxploitation era.