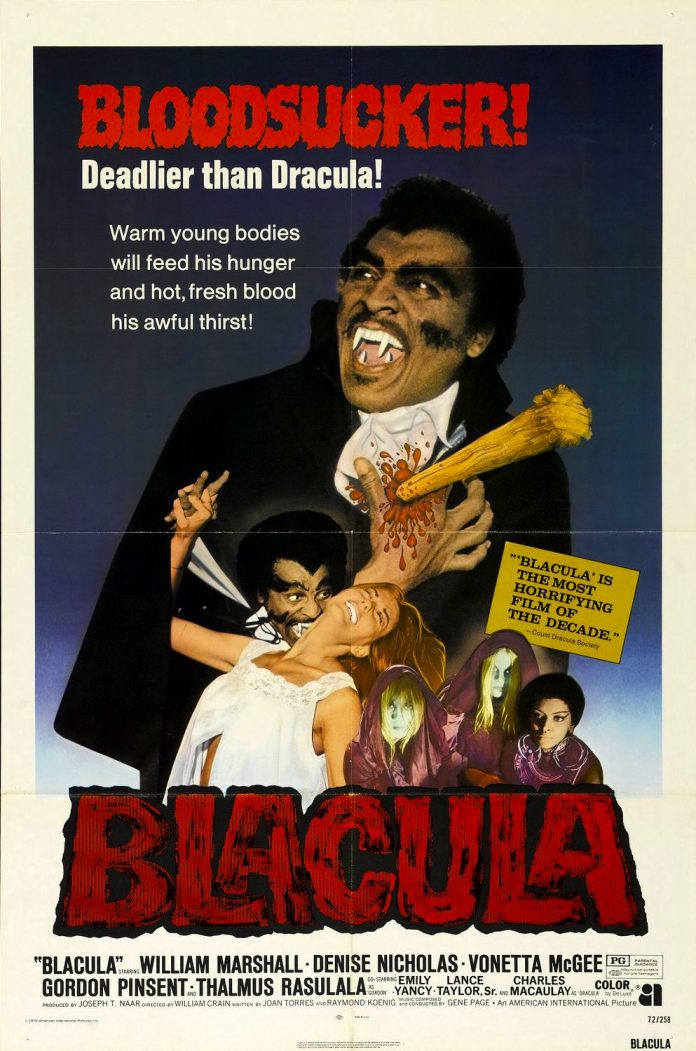

Blacula has become synonymous with black horror — and rightly so — but beyond being a seminal film that kickstarted the modern concept of black horror, it was also one of the earliest and most successful movies in the influential “Blaxploitation” era of cinema, propelling a movement that satiated a need to see faces of color in starring roles on the big screen.

Plus, it’s also just a damn good movie. Budgetary limitations and ’70s-era fashion aside, it’s well-acted and atmospheric with a few genuinely creepy moments (the slow-mo scene in the morgue is still unnervingly effective). Judging by the title, you’d guess that any enjoyment derived here would be campy (I suppose the filmmakers couldn’t resist the punny title; Mamuwalde isn’t quite so catchy.), but it’s played remarkably straight, and the booming presence that is William Marshall sells it for all it’s worth.

In it, Mamuwalde (Marshall) is an 18th-Century African prince who travels to Transylvania to ask Count Dracula if he would mind not enslaving his people…pretty please? Dracula, being the bastard he is, sucks his blood and kills his wife (Vonetta McGee). Fast-forward 200 years, and for some reason, there’s a yard sale at Dracula’s castle. Two (unfortunately flaming) Los Angeles interior decorators scoop up Mamuwalde’s coffin, bring it back to the US, and it’s on! As is now the standard in century-spanning gothic horror, Mamuwalde just happens to come across Tina, who looks exactly like his dead wife. Heartbreak and polyester ensue.

From scenes of Mamuwalde fighting slavery at the beginning of the film to him fighting (white) cops at the end, Blacula was no doubt a crowd pleaser for its target audience, reflecting the Afrocentrism of the early ’70s. (Fun fact: It was Marshall’s idea to make the character an abolitionist African prince. In the the original script, his name was Andrew Brown…the same as a character from Amos ‘n Andy.) It was also notably one of the few Blaxploitation films of any genre to have a black director — the great William Crain, who went on to helm another standout black horror movie with a social conscience hidden beneath a cheesy title: Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde.