I feel like at one point, Blackstock Boneyard’s intention was to be taken seriously. Marketed as being “in the tradition of Candyman,” it was originally titled Rightful, which sounds like either a Civil Rights Movement period drama or a Kirk Cameron right-to-life wet dream. It’s based on the true story of brothers Thomas and Meeks Griffin, successful Black farmers who were wrongfully convicted and put to death in 1915 for the murder of a White man named John Lewis. In real life, they were pardoned posthumously in 2009 after lobbying by radio host Tom Joyner and historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the latter of whom revealed in the PBS series African American Lives that the former is a grand-nephew of the Griffins. That was the first time in history that South Carolina had issued a posthumous pardon in a capital murder case, and it *CHECKS NOTES* officially ended racism in the state.1

1Source pending

However, in the movie, re-titled the appropriately horrific Blackstock Boneyard, justice comes in more Vorheesian fashion. The Griffins return from the grave a century after their deaths to enact violent retribution on the descendants of the trio who set them up: the judge who convicted them, the D.A. who tried them and the witness who testified against them: a Black woman named Anna Davis (Brittany Lucio) who, in the film, claimed that the brothers not only killed Lewis, but also raped her. When the Griffins were forced to sell their extensive land holdings to pay for their defense, the three conspirators acquired the property. (In real life, Davis was not raped and was not a witness. She was employed by Lewis and was supposedly having an affair with him, but the fact that she was 22 and married and he was 75 certainly calls into question how consensual that relationship was, thus providing ample motive for Davis or her husband to be the culprit.)

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and big-box store Savemart wants to buy the Griffins’ former land. Descendants of the judge, CJ Ramage III (Terry Milam), and the D.A., Roger Newbold (Jonathan Fuller), are eager to sell their shares, but they discover that there’s a long-lost relative of Anna Davis who has to sign away her portion for the deal to go through. Her name is Lyndsy (Ashley Whelan), and until now, the only Black bone she knew that was in her body happened during the 2018 NBA All-Star weekend. Zing! But seriously, when she hears about all that Savemart money, she heads to Blackstock, South Carolina with three friends in tow to meet up with CJ and Roger.

CJ is a ridiculously caricatured Southern racist who, clad in a white suit like an alt-right Colonel Sanders, casually slaps Black workers and calls them “boy” while threatening to have their “Black asses fired.” He’s actually par for the course as far as the White townies in the movie go; there’s a scene with three of them drinking a toast to “White pride” at the local bar before casually deciding to go lynch a Black man. Then, a pair of White cops stumble upon the scene but turn a blind eye to the hate crime in progress as if it was just a case of public urination. Luckily, the undead Griffins arrive in time to kill the White supremacists before the hanging, and later they kill the cops to boot, but those are just side missions for the zombie brothers, who have their sights set on Lyndsy, Roger, CJ and CJ’s kids, Corey (Bryan McClure) and Samantha (Laura Flannery), who seem to have a “sibling with benefits” relationship…?

Meanwhile, Lyndsy gets the “White version” of history from an old lady who calls the Griffins murderers and rapists who got what they deserved, but when Lyndsy meets one of their descendants, Jesse (Aspen Kennedy Wilson), he explains that his ancestors were framed. It’s thus up to Lyndsy to decide whether to take the “blood money” or to figure out a way to make things right with the rampaging brothers from beyond. Her solution, it turns out, isn’t far from the NBA All-Star Weekend scenario after all. *SPOILER ALERT* She not only voids the contract to sell the land by shooting CJ in the head (Some might call that murder, but I’m no legal expert.), but she also seemingly agrees to share the property with Jesse (who saved her life), and they move in together, smooching as the credits roll. So…if she DIDN’T find Jesse attractive and they didn’t hook up, would she have just kept the land for herself? Would that have satiated the Griffins? And what happens now if they break up — a likely outcome since they’ve known each other for, like, ONE DAY. If they split, will Thomas and Meeks rise from the grave again to make sure the land stays with their family? That would be one hell of a divorce lawyer. *END SPOILER*

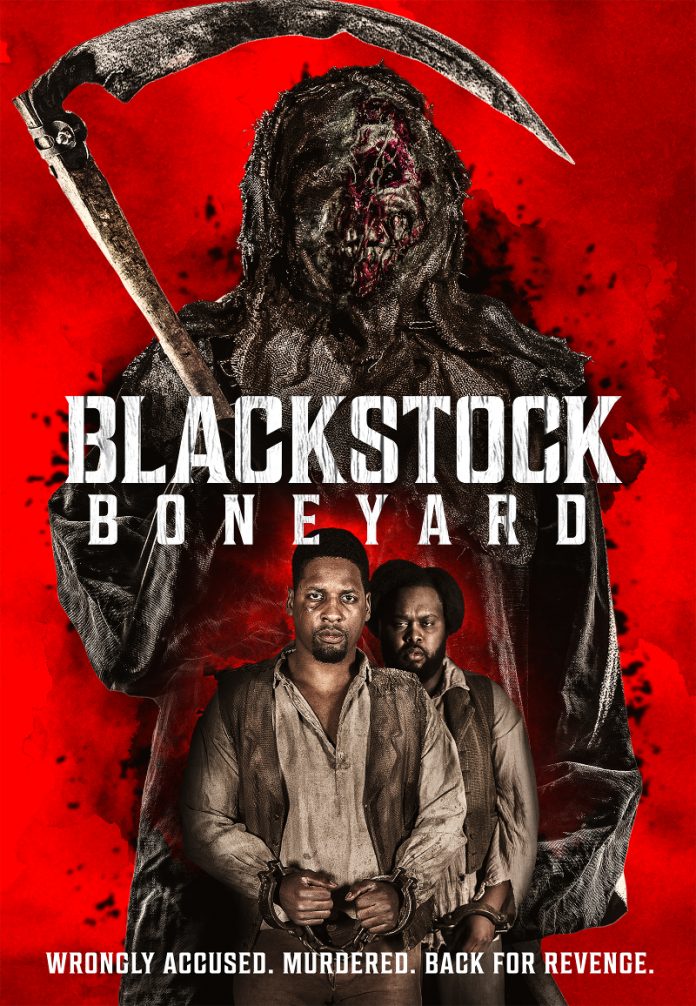

Despite being based on a real-life case and dealing with racial topics that inherently carry a level of gravity, Blackstock Boneyard plays like a straightforward, low-brow slasher — and not a particularly good one at that. It does boast a key slasher element, however: memorable killers with a compelling backstory and intimidating character design. Dressed in the clothes they wore to their execution (complete with a sack over their heads) and carrying tools of their farmer trade (scythe, pitchfork…um, whip?), the Griffin brothers cut striking figures worthy of headlining a horror movie. However, the film undermines their potential with rote kills and the inexplicable use of CGI blood splatter. The acting is too amateurish to sell the material, which raises the question of the appropriateness of mining a real-life tragedy for cheap thrills in the first place. It might not be as bad as having a zombie Emmett Till return from the grave for revenge, but it’s a slippery slope. (The director, Andre Alfa, it should be noted, is not Black, but I’m not sure if writer Stephen George is or not.)

The movie does make sure to paint the Griffins in a sympathetic light, even as they hack and slash their way through town. The only people they kill are portrayed as terrible: either racists or assholes descended from racists. (Incidentally, they’re also all White, whereas the only Black people who die are the brothers themselves — a reversal of the typical horror film scenario.) Although Lyndsy’s three friends die, the filmmakers take pains to ensure they’re not dispatched by the Griffins — with unintentionally hilarious results, such as one friend turning to run from the killers and tripping after taking ONE STEP, then hitting her head on a conspicuously placed INDOOR boulder. Another friend somehow reasons that it’s preferable to slit her own throat with a rusty scythe rather than fall prey to whatever she envisions the Griffins have in store for her (shades of Flora leaping from a cliff in The Birth of a Nation?).

Despite its flaws, Blackstock Boneyard makes the most of its modest budget with a nice overall look and atmosphere, and with a running time of barely 80 minutes (including credits), it’s a quick, easy watch, which is more than you can say about some tedious dreck out there.