In the year 2022, unemployment and crime are down to historic lows, thanks to an annual ritual known as the Purge. During the 12-hour event, which commences at sundown and ends at sunrise, all crime (with a few noted exceptions, such as assassinating high-ranking government officials) is legal, and if you find yourself injured or under attack, don’t bother calling 911 because no one will help you. The ostensible purpose of the Purge is to allow people to blow off steam and to funnel the natural human inclination towards violence, but detractors claim that it’s a form of elitist genocide in which those who can’t afford gated mansions with high-tech security systems end up dying.

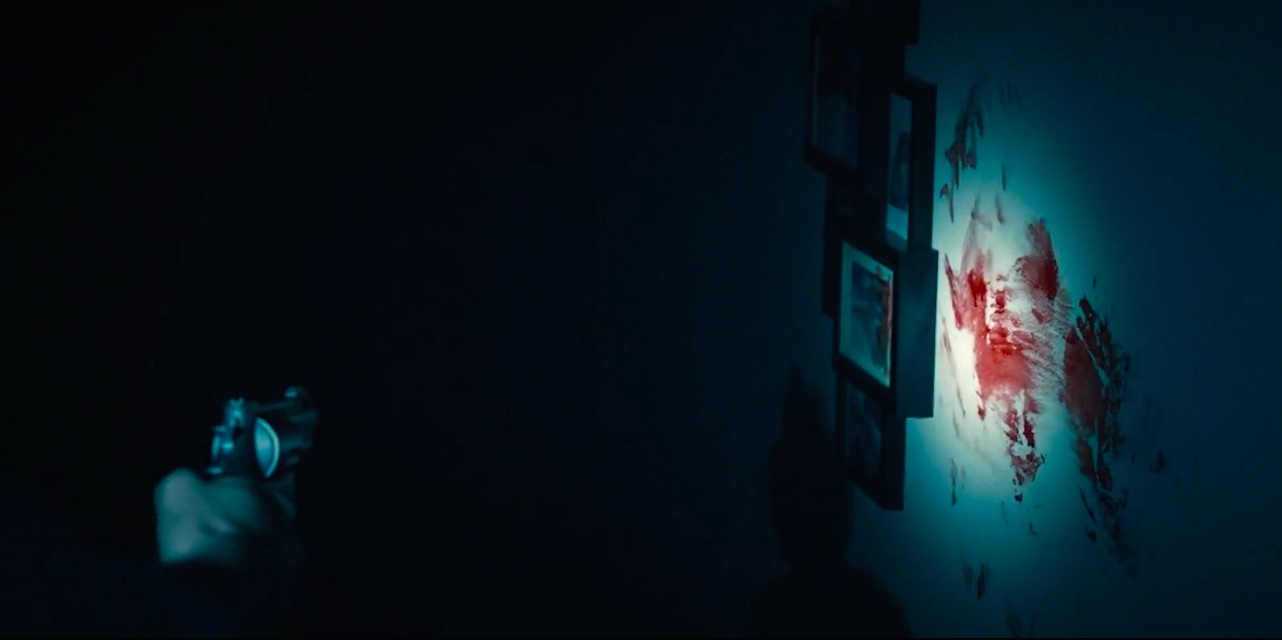

James Sandin (Ethan Hawke) is the man responsible for a good number of such security systems, having enjoyed a record year of sales of the high-tech devices. He’s thus in great spirits as the evening of the latest Purge arrives and he settles in for what he thinks will be a quiet night in his gated community with his wife Mary (Lena Headey), rebellious teen daughter Zoey (Adelaide Kane) and techno-geek son Charlie (Max Burkholder). But when a wounded stranger (Edwin Hodge) comes knocking, pleading for help, and Charlie decides to let him in, all Hell breaks loose as James must figure out not only if this man is dangerous, but also how to deal with the bloodthirsty masked individuals gathered outside his house demanding the Sandins return the stranger to them.

For a horror movie, The Purge has an unusually high concept, its speculative nature bordering on futuristic science fiction and its underlying social commentary a welcome jolt to a genre that at this point was dominated by formulaic ghost stories. Ostensibly, it deals more with classism than racism — race is never specifically discussed — but the bloody elephant in the room is the fact that the wounded stranger is black, while his attackers and the Sandins are all white.

With such a racial disparity, it’s not hard to read an old-fashioned lynch mob vibe into the scenario, which gives the unspoken impression that the “have-nots” who are most susceptible to the Purge because they can’t afford to live in gated communities with high-tech security systems are people of color. (The entire community appears to be white except for one black woman and one Asian man.) Writer/director James DeMonaco, who wrote the remake of the similarly plotted (minus the social commentary) Assault on Precinct 13, thus manages to make a powerful statement about race without actually talking about race.

Upon my initial viewing of The Purge, I actually didn’t enjoy it because I was expecting something along the lines of The Strangers, when in fact it aimed for something much deeper than that nihilistic (though excellent) slice of cinema. Rewatching it, I came to appreciate the sociopolitical implications as well as the action and thriller elements, even if the less-than-intimidating masked villains come off as drunken frat boys with hearing impairments (Seriously, why don’t they all just converge on the sounds of the gunshots?). Surprisingly, for a film set during such a bleak annual event and in such a bleak genre, it somehow manages to end up with an upbeat, borderline kumbaya culmination — something that might be harder to do in 2018 than it was in 2013.

The Purge movies aren’t subtle, but politics isn’t subtle these days either, and to make such clear political statements of the dangers of giving into humanity’s worst instincts is something not a lot of mainstream movies, never mind genre movies, are trying. Presumably the big studios are too chicken about alienating any potential customers, but The Purge series is refreshingly blatant about it, and I admire them for that.