Even for hardcore horror fans, found footage movies have pretty much worn out their welcome. Too often, they feel like an easy way for someone to make a film on the cheap without having to account for polished camerawork, effects, editing or dialogue. And too often, they show little concern for originality, trotting out the same scenario over and over again. How many times can we watch a group of people investigate a haunted building and end up dead or missing, leaving only video evidence of their ordeal? By my count, 367.

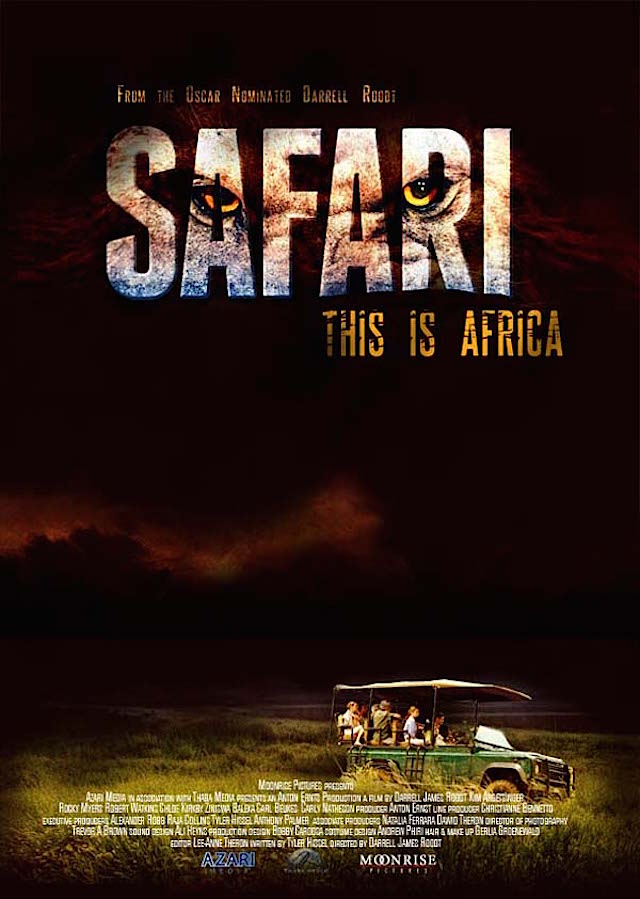

For all of its faults (of which there are numerous), Safari does at least manage to stand out in this crowded sub-genre for one unique element: its setting. As the title implies, the movie takes place during an African safari, meaning we don’t have to suffer through another clichéd haunted house and/or abandoned asylum jump scare-fest.

We are, however, subjected to the same sort of mundane content that dooms the worst of this type of film: banal banter from bland characters, uneventful, ad-libby dialogue meant to replicate “real” conversations and long stretches of inactivity punctuated by brief, ineffectual scares. Plus, there’s the ever-present issue of why someone would be filming all of these scenes; even beyond the animal attacks (during which people should drop the camera and run), why the hell would you film someone grieving over the death of their spouse?

Setting it in the wilds of Africa, of course, means trotting out the old stereotype of the continent being one big open-air zoo full of wild animals (and wild people) around every corner waiting to kill you. (The film’s tagline “THIS IS AFRICA” certainly doesn’t help.) Here, we get lions, snakes, hyenas, elephants, zebras, leeches and even a non-Marvel black panther. The creatures menace a group of tourists — the main foursome from America and another four from South Africa (all white) — whose tour guides (both black) decide to take them from the safety of the reserve into an area designated for hunting because the group simply HAS to see some lions.

This being a horror movie, of course their vehicle becomes disabled in the middle of nowhere, and one guide quickly gets killed by an animal while the other high-tails it out of there, leaving the tourists to fend for themselves. Thanks to these two irresponsible louts, it initially seems the black characters in the story will be disposable tools, functioning merely to set the ball rolling on the inevitable mayhem, but the group comes across a young girl from Mozambique named Mbali (Ziniswa Baleka) who’s likewise lost in the wilderness.

Mbali has a sob story that puts the group’s to shame. On her deathbed, her terminally ill mother sent her and her siblings on a cross-country trek on foot to live with their aunt in South Africa, but along the way, the children were attacked by lions, and only Mbali survived. Thus, despite speaking few lines of dialogue (She doesn’t know English.), the little girl becomes the central figure whose survival is the emotional core of the film.

Unfortunately for her, the group isn’t exactly full of Bear Gryllses. Even though they have a map, they can’t figure which direction they should go — even when they encounter pretty obvious landmarks like rivers and mountains. At one point, a helicopter flies overhead, and they don’t even think to light their flares. And frankly, they barely even need the animals to ensure their doom; when they aren’t having heart attacks or falling off cliffs, they literally SHOOT THEMSELVES IN THE FACE.

Luckily, Mbali knows some tricks of the trade for survival, and she actually ends up helping them as much as they help her. And, in a rarity for a found footage film — SPOILER ALERT — she actually ends up living through the experience, and as the sole survivor, she’s responsible for delivering the footage to the US State Department in South Africa. *END SPOILER*

The most impressive (or criminally reckless?) part about Safari is how close the actors and camera operators seem to get to the wild animals in real life. It looks like they literally just went on a real safari and filmed a movie over the course of a couple of days. I guess the film is something of a success for its ability to convey that sort of realism, but in virtually all other ways, it’s a dud. Perhaps because they did shoot it on a safari, the animal attacks are few and far between (since they couldn’t exactly control them), and the footage of the attacks is murky and disorienting.

There’s an attempt to toss in an interesting “don’t mess with Mother Nature” message about big game hunting — one character opines, “They’re hunting us because we hunt them…We deserve it.” — but it’s dealt with in a throwaway manner, and the shoddy quality of the movie makes it ring hollow anyway. Veteran South African director Darrell Roodt has helmed films as high-brow as Cry, the Beloved Country and as low — er, no-brow as Dracula 3000, and while Safari doesn’t stoop to that level, being better than Dracula 3000 isn’t exactly high praise.