Shockumentary, or “mondo”, films are trash. There, I said it. Some people love their sleaziness, some (I’d guess most) don’t. I fall into the “don’t” camp, and although I wouldn’t lump them together with fictional horror, that’s where they’re generally found in the video store, so I figured I’d go with the flow.

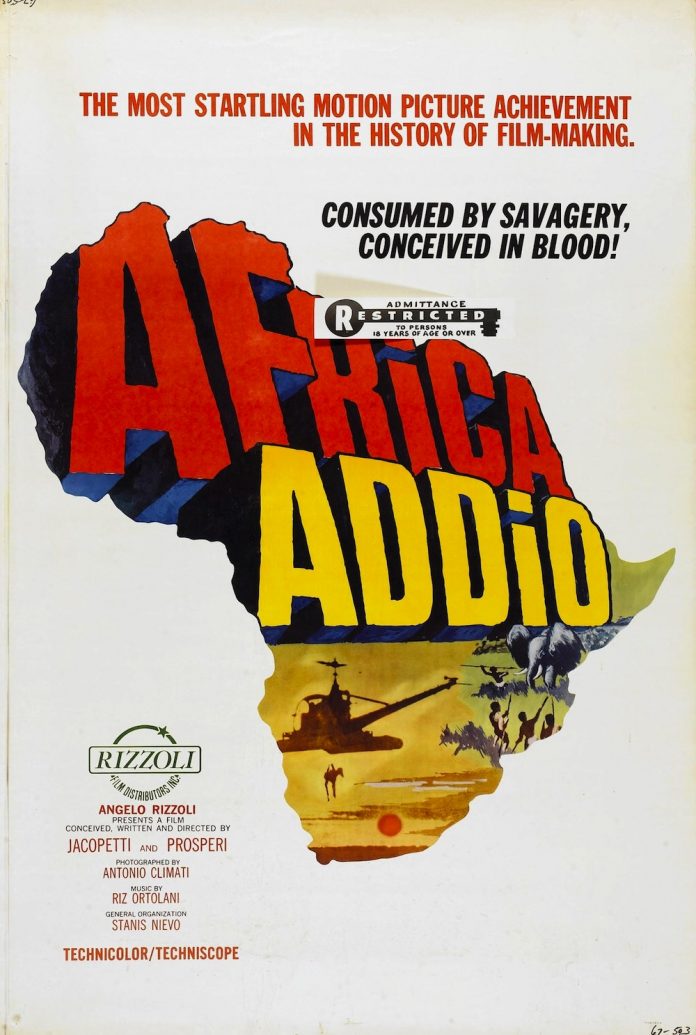

The Italian Mondo Cane series began the phenomenon in 1962 and is still one of the more well-made and “classy” (relatively speaking) of the genre. The first three films of the series briefly touched upon Africa alongside other worldly “weirdness”, but the fourth, Africa Addio (re-cut in the US as Africa Blood and Guts), deals exclusively with the continent.

To say it was controversial at the time of its release is an understatement; it was denounced as racist and exploitive and either banned or severely edited in the countries in which it was shown. Even without the racial overtones, though, it’s easily the most difficult to watch of the Mondo Cane movies, unless you’re into viewing the wholesale slaughter of people and animals for a mind-numbing two-plus hours. (To be fair, there’s a good 30 minutes or so without anything dying…except my faith in humanity.)

Ironically, it’s a beautiful film from a technical standpoint, shown in vivid color with striking cinematography and intense close-ups that put you inside the action…which makes it all the more disturbing. I honestly think that filmmakers Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi were well-intentioned in making this film, purported to be an exposé of the atrocities being committed following the European decolonization of Africa. The scenes documenting the ethnic strife and genocide are riveting, important and fascinating from a historical standpoint, but the Italians’ unintentional racial bias comes through in condescending voiceovers like:

Europe is in a hurry to leave and on tiptoe even if, all things considered, it has given far more than it has taken. Europe, the continent that nursed Africa, can no longer manage this big black baby that grew too quickly, keeps bad company, and what’s more, hates it because of its white skin. And so it is abandoned, still cranky and immature, just at the moment when it needs Europe the most.

Or:

The female African has discovered she is a woman and is beginning to behave as such. She wants to be modern because she feels the past is against her. When she was naked, she had two mammary glands. Now that she’s clothed, she has two breasts. She does not want to display herself. She wants to be looked at to make you guess what’s under her alluring clothes. She covers her intimacy not out of modesty, but to be flirtatious. She undresses to surrender and dresses to attack.

This latter monologue is read, incidentally, while the camera peeks into a dressing room full of half-clothed African women, one of the scenes that seriously undermines any semblance of journalistic integrity that the film establishes. (The scene of lions humping to wacky music doesn’t help, either.)

Also casting doubt is the fact that, while most of the footage is real, some is jarringly staged, such as a gratuitous montage of white South African women tearing their clothes off as they run Baywatch-style along the beach, then swing on swings and…jump on trampolines? When did this turn into Spike TV? And what about when they show a behind-the-scenes look at a film being shot with black extras who, during a break, “spontaneously” burst into song and dance, pulling out an entire drum set, an upright bass and a piano (!) for a well-choreographed performance.

Then, there’s the animal footage. They would have you believe the scenes of slaughter are intended to emphasize the struggles of the transitional period from colonization to independence, but they come off as sensationalism: Is seeing 10 elephants or gazelle or zebra killed not enough to prove the point? Do we really need 20? 30? 50? All in graphic detail? And showing an unborn baby hippo being pulled from its dead mother’s belly? Classy. Plus, the filmmakers don’t distinguish between the unchecked poaching for horns and the controlled, once-a-week hunting for food that’s imposed by the new government; all of the killing is shown as a gory indication of the downfall of Africa.

The Italians’ vision of what Africa is, though, seems overly romanticized; they seem to wish that the entire continent was filled with naked natives without a trace of modernization. Plus, their Eurocentric viewpoint glosses over how colonization contributed to the continent’s social, economic, religious and racial discord. One voiceover even seems to imply that both sides of the Apartheid racial divide were on equal footing, calling both white Johannesburg and black Soweto “gilded cages” for the races.

Alternately fascinating and repugnant, Africa Addio is a draining experience, a powerful time capsule whose value is tempered by prejudice masquerading as objectivity, oversimplification masquerading as fact and shock tactics masquerading as journalism.