Originally written for Salem Horror Fest

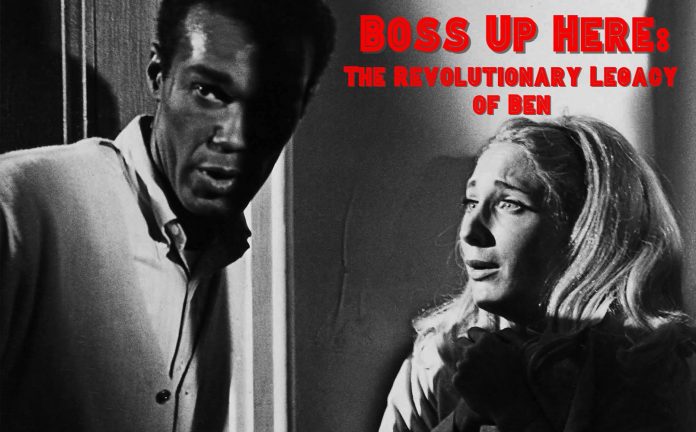

One of my earliest memories of genuine horror fandom came in the mid-’80s when I popped a VHS tape of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead into my family’s VCR and watched as the character Ben (Duane Jones) led a ragtag group of strangers in their effort to survive a zombie siege, barricaded inside a remote Pennsylvania farmhouse. He was brave. He was take-charge. He was intelligent. He was handsome. He was heroic. And he was black.

It was the latter in particular that drew me to him, because he was somebody who looked like me, and people who looked like me historically didn’t play roles like Ben. Frankly, in the 1960s, apart from Sidney Poitier, there were scarcely any black stars headlining mainstream movies, and within the horror genre, you’d be hard-pressed to find ANY black actors or actresses — stars or otherwise.

While the Blaxploitation era of the ’70s provided greater exposure for black cast members, it was a largely segregated movement, and by the time I sat transfixed by NOTLD in the ’80s, black leading roles were once again scarce in Hollywood. Aside from megastars like Eddie Murphy or Whoopi Goldberg, the best black actors and actresses could hope for was a gig as a sidekick. More likely, they’d be Mugger #2 or Foul-Mouthed Hooker, and in horror, this marginalization manifested itself in an especially drastic manner: death. This was such a common occurrence, in fact, it became a running joke within American pop culture that in horror movies, “the black guy” always dies first.

And so, as I watched this zombie classic, which had so many great things going for it — a legendary director making his debut, edgy gore effects that would signal a shift in genre aesthetics, a redefinition of zombie lore that would serve as a template for the next half century — it was this plucky black man who inspired my awe and showed me how a genre as critically reviled as horror could actually be socially relevant and, dare I say, revolutionary.

It was stunning to me to watch this black-and-white film from the 1960s, populated by actors who looked like they should be in a newsreel about the Civil Rights Movement in the Jim Crow South, but rather than the black man being hosed by policemen or attacked by dogs, he was the one in control. He was the undisputed leader of this group, barking orders at white people and daring to get physical with them if necessary. “Get the hell down in the cellar,” he tells the obstinate Harry. “You can be the boss down there; I’m boss up here.” Even if it had been set in the same era in which I was watching it, this portrayal would’ve been a revelation.

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of Ben’s role in normalizing black leads in Hollywood movies (granted, that remains a work in progress). Its popularity helped paved the long, circuitous route towards what some have called a new Harlem Renaissance in cinema today, boasting an unprecedented mix of commercial and critical success for movies with black headliners. (In the 70 years the Academy Awards were held during the 20th century, there were 16 nominations and one win for black talent in the Best Actor/Actress categories. In the two decades since 2000, there have been 19 nominations and four wins.)

Because Ben was written as white, NOTLD was one of the first films of any genre starring black actors or actresses that didn’t have a plot specifying their race. Although Romero hired Jones through a color-blind audition process, however, the impact of his color was not lost on Jones, who later stated, “It never occurred to me that I was hired because I was black, but it did occur to me that because I was black, it would give a different historic element to the film.”1

Thus, Ben’s tense interactions with the white characters, the sense of rage he emanates throughout the film and the shocking ending — in which he’s killed by a group of white authorities akin to a lynch mob — all carry racial overtones unprecedented in horror that are still quite potent, regardless of genre. The somber ending in particular helped establish a pessimistic tone for zombie movies to come, while simultaneously reflecting the racial reality of an era in which assassinations and riots had replaced sit-ins and marches (Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death having occurred just six months prior to NOTLD‘s premiere).

In fact, when Romero was considering filming an alternate ending in which Ben doesn’t die, Jones lobbied against it. He knew Ben could serve as a symbolic martyr of sorts for African Americans. “I convinced George that the black community would rather see me dead than saved, after all that had gone on.”2

More than 50 years later, as racial unrest once again scorched American soil in the wake of a series of high-profile incidents of police brutality, perhaps there was no better testament to the enduring legacy of Ben’s death than the homage paid to it at the end of Jordan Peele’s 2017 horror hit Get Out. In it, the black hero, having survived the onslaught of the film’s primary antagonists, is approached by the flashing lights of what appears to be a police car — raising anticipation that, like Ben, he will be gunned down by overzealous authorities. Unlike Jones, however, Peele felt that the on-edge nation needed an ending “that gives us a hero, that gives us an escape, that gives us a positive feeling,”3 so he opted for a happy resolution and cause for optimism — an alternative, it could be argued, made possible by the example set by Ben half a century earlier.

1 Joe Kane, Night Of The Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever, 32.

2 Kane, 36.

3 Nigatu, Heben and Tracy Clayton. “Incognegro”. Another Round. Podcast audio, March 1, 2017. https://www.acast.com/anotherround/episode-83-incognegro-with-jordan-peele.