When I was in college, I took an African history class in which my professor went on a tirade about how much she hated the movie Congo. I can’t remember the specifics of why, but let’s just say at the very least that the historical accuracy of the story of King Solomon having Sub-Saharan diamond mines guarded by trained killer gray gorillas is lacking.

Congo is a throwback — for better or worse — to the “wilds of Africa” films of yesteryear, from adventure tales featuring Tarzan and Allan Quatermain to fright flicks like Monster from Green Hell and Curse of the Voodoo. The legend of King Solomon’s mines, in fact, has been fodder for fantastic tales since the first Allan Quatermain book back in the 1880s.

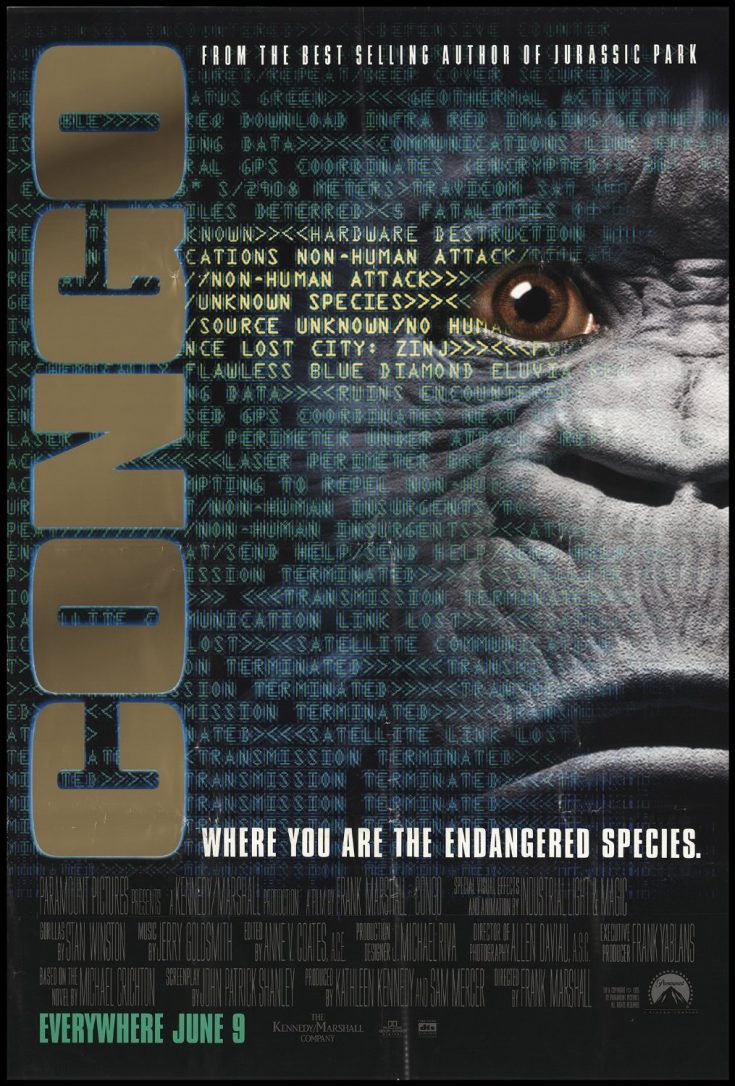

With Congo, Paramount no doubt hoped to tap into the same sort of throwback adventure nostalgia that fueled the success of the Indiana Jones films in the ’80s, while continuing to milk the hit-producing potential of author Michael Crichton, upon whose book Congo was based and whose Jurassic Park had just set the box office aflame two years earlier. The studio even hired frequent Spielberg collaborator Frank Marshall, who lent that Spielbergian touch to Arachnophobia, to direct.

The result isn’t nearly as good as Arachnophobia and plays like what you might expect from a poor man’s Spielberg. It has some entertaining spots — particularly the final battle of man versus ape (although I still can’t figure out how a telecommunications company has diamond-fueled laser guns lying around) — but Congo buys so heavily into the “lost world” trope that it ends up recycling the fetishization of Africa that made such earlier films so problematic.

In Congo, Africa remains the Dark Continent of yore, with animals thirsting for human blood around every corner (including hippos, which in fact are quite dangerous but cinematically come off as a bit goofy) and primitive tribesmen engaging in mysterious, gyrating rituals.

This reincarnation of Darkest Africa, however, also introduces a modern threat: civil war. The moment the American protagonists get off the plane in Africa, there’s a car bomb, a carjacking and reports of rebel cannibalism, and later they have to bribe a corrupt militia leader (the sorely underutilized Delroy Lindo), evade roadblocks with soldiers seemingly ready to execute at the slightest provocation and dodge surface-to-air missiles while flying across the border.

Newsreels of African wildlife that titillated Americans in the early 20th century had, by the late 20th century, been replaced by news reports of African warfare and internal strife, and fictional cinema like Congo fed both from and into that imagery.

Unlike the much superior The Ghost and the Darkness, which portrayed its killer animals (in that case, man-eating lions) as symbolic repercussions of European colonialism, Congo doesn’t feel that literate and only briefly touches upon the racial ramifications of colonialism in a scene in which a pair of tribesmen are skeptical that Munro (Ernie Hudson, whose role was smartly changed from Caucasian, avoiding a mortal fate for every black member of the hunting party) could be the leader of the expedition because he’s black.

If I were in a militant, English-majoring mood, I might venture into interpreting the gray gorillas as African natives corrupted by interloping, greedy humans (Europeans) who trained them to be violent and ended up being overthrown, leaving the riled-up apes to fend for themselves, attacking other nearby gorilla troops. Then, of course, arrives a “good” gorilla from America named Amy who’s been taught sign language and, using motion recognition technology, can actually “speak” like a human (with a cloyingly cute, computerized little girl voice), making her the type of “civilized” ape the humans like — even though all the “bad” gorillas are doing is protecting their turf and acting in a manner for which they were bred. (In the book, the human masters actually mated with the gorillas, which leads down a whole other path that would require therapy.)

Perhaps inbred self-hatred explains why, when the volcano on which the gorillas live conveniently erupts just as our heroes are making their escape, the gorillas start doing cannonballs into the lava like they’re at a damn high school pool party.